Mary Ellis was kind enough to send me the above photo of china which Grace Hogg (abt. 1777-1853), Thomas Sutherland’s second wife, brought with her when the family emigrated to Canada in 1833. There’s something about the peonies and delicate gold details that made me think about Grace’s upbringing in a house of significant wealth—even if it wasn’t hers.

There have been conflicting reports about Grace’s origins. Known historical documents are limited to those from Canada, and the report of her

marriage in Edinburgh Parish, Edinburgh, Midlothian, Scotland. Winning Pendergast’s version of her antecedents is the one most frequently cited. As Pendergast writes:

“Upon the death of his first wife, he married the Honourable Grace Hogg, daughter of an English Admiral whose home, near Edinburgh was called “Lasswade.” Grace (Hogg) Sutherland had two brothers, Charles and Adam Hogg. The latter became General Adam Hogg of the Army in India. General Hogg married Agnes Dinwiddie, niece of Sir

Robert Dinwiddie, one of the last Royal Governors of the colony of Virginia.”

While certain parts of the above can be documented, other elements reflect the inaccuracies that often sneak into family stories as they are orally transmitted through generations. Notably, if Grace’s father was an Admiral, she would not have been granted the title “Honorable.” And, given the conventions of the time, if her father was in the navy, it makes no sense that her brother entered the army. Additionally, there is no Admiral who fits the bill. But, most tellingly, if Grace’s brother was Adam Hogg—as it appears he was—then her father was definitely not a military man.

In a letter to his sister Grace, dated October 26, 1797, Adam Hogg writes: “I have this day passed the Court of Directors of the

East India Company and am now a cadet. Please inform our mother of the circumstances.” Adam and his sister appear to have been close: a miniature of him, with his correct birth and date of death, was passed down in the family. Also passed down was Agnes Dinwiddie’s sewing basket, though its current whereabouts are unknown (it was last in the possession of Marjory Doble Bryson. As always, suggestions welcome).

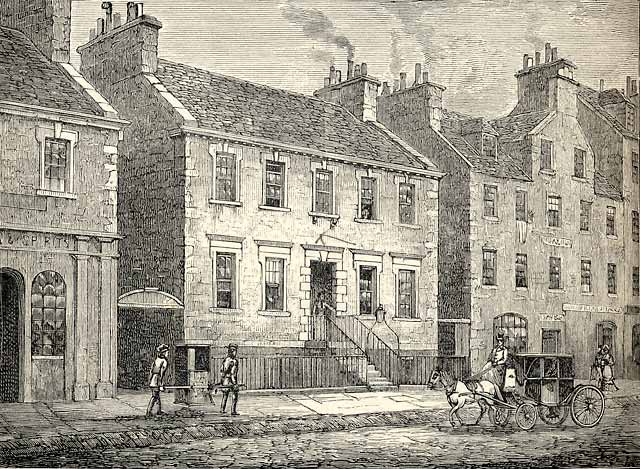

There is an excellent Hogg family researcher, Eleanor Donaldson, who has documented Adam Hogg’s family. It is because of her work that we know Adam was the son of George and Isabel Hogg, George being the butler of

Henry Dundas, Viscount Melville. I have consulted all available published works on Dundas for even a passing reference to his butler, but to no avail. I prefer to believe that this is because George Hogg was so efficient as to never merit notice: this is, after all, the hallmark of a successful butler. Certainly, he would have had ample opportunity to showcase his talents. According to one historian of Dundas, “His social qualities, his generous hospitality, and the excellence of his wine cellar, made him a splendid host, and his parties were frequent and large.” This, of course, all translates into more work for the staff.

Being the daughter of a butler would have certain advantages: generally such girls were educated, sometimes with the children of the family, if they were of an age. According to one story, Grace Hogg was familiar, even friendly, with the Dundas children, though she was at least five years younger. The proximity of the Hoggs to the Dundases would have also instilled in them a knowledge of the manners and customs of upper class families, which they might themselves adopt. It was thus not unusual for such the butler’s daughter to be perceived of as a lady in her carriage and demeanor. And yet, as one Edwardian commentator noted, the butler’s daughter suffered her own plight, namely an “exceptional endowment [which] has made distasteful the suitors of her own walk of life.” This author noted that she was unlikely to marry.

Still, others noted that the butler’s daughter had her own resources: for example,

Thackeray, in

Vanity Fair, suggests that propinquity breeds opportunity, in representing Miss Horrocks as mistress to the master. More kindly, he was said to have remarked (in relation to the tendency of the peerage to intermarry) that they would have been bred to extinction if every so often someone in the line of succession had not eloped with the butler's daughter.

If the parish record of May 15, 1825 is correct, Grace Hogg was certainly older than the average first-time bride. But taking into consideration her education and knowledge, she would have still been a catch for an ambitious man, and Sutherland appears to have wasted no time in pursuing her, given his first wife’s

death not quite nine months before.

There is much more work to be done on Grace and the Hoggs. But if you are interested in learning more about the dynamics of the staff in a large house, as well as the role of the butler, I would highly recommend the BBC series,

The Edwardian Country House (in the U.S. it aired as

Manor House). I recognize that it is Edwardian, and thus in some ways anachronistic as a framework for Grace’s upbringing. And yet, the series makes the argument that not much changed: that was the whole point.